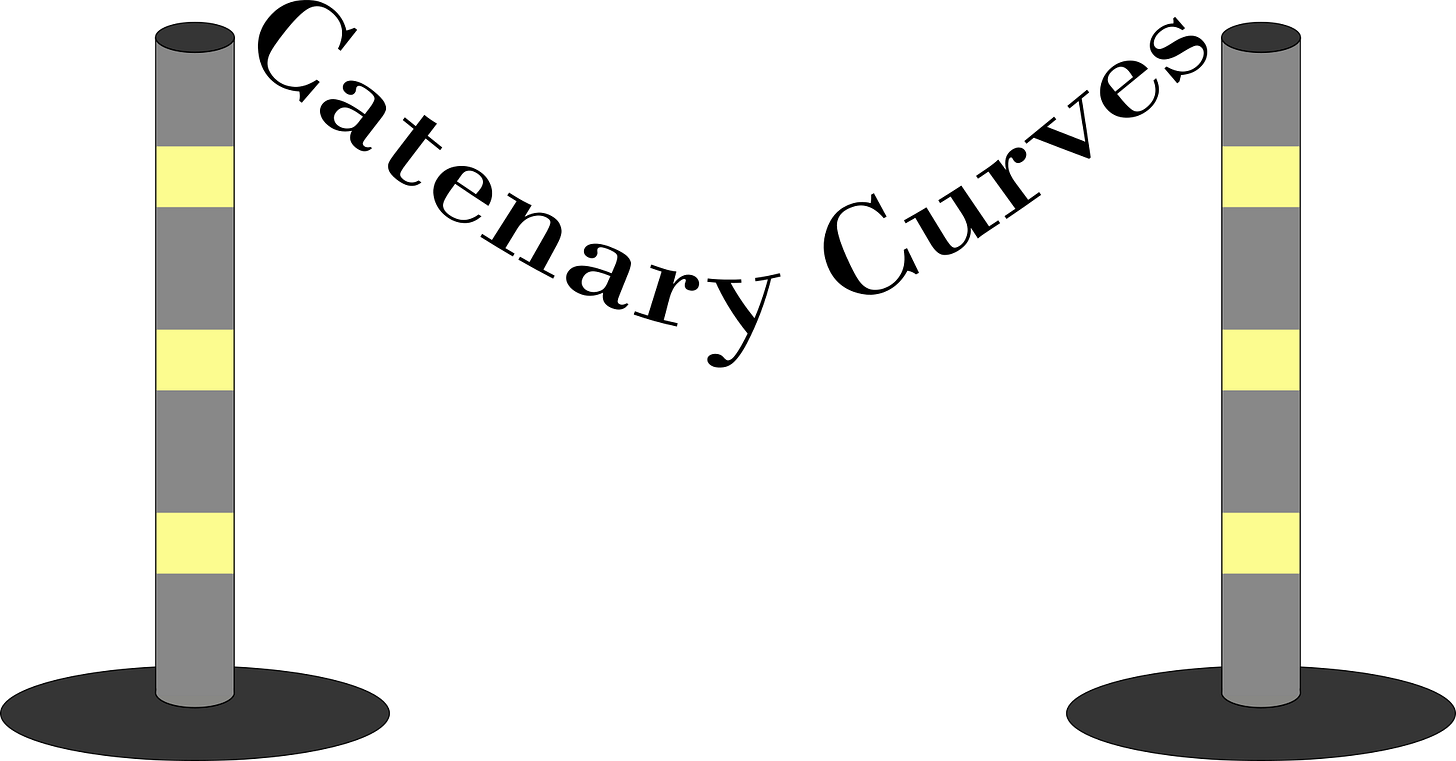

Catenary Curves

Once you see them, they’re everywhere.

Many of my readers will be familiar with the mathematics behind shapes seen in nature: the golden ratio, parabolic paths of objects under gravity, hexagons in honeycombs, snowflakes, and basalt columns, for example. Anyone into astronomy might have thought of the analemma, but that one’s a little niche.

Either way, another shape you’ve seen countless times in the last week – without even realising, I might add – is the catenary.

As the picture may have suggested, a catenary is the shape of a rope hanging between two points that aren’t directly above or below each other. This means that every roped-off area, power line, clothes line, hammock (not including ropes) or even untied shoelace, among many other things, are all catenaries.

Admittedly, this curve looks very similar to a parabola, particularly on the scales you’d see it in everyday life, but its properties are slightly different, and as you look at a larger section of the curve the difference becomes clear. I made an interactive representation of the catenary against the parabola to help with this, along with a quick animation.

A bit of Maths

Before I get into the other uses for this shape, the equation for the catenary is:

For any budding mathematicians who want to derive this themselves, start with looking at forces on a section of the chain, then making a differential equation. At some point you’ll need to use definitions for hyperbolic trig, which, for UK sixth-form students, is a nice foray into Further Maths A-Level, and may be interesting anyway.

If that’s too much bother you can also search up the full derivation of the equation.

Other Uses

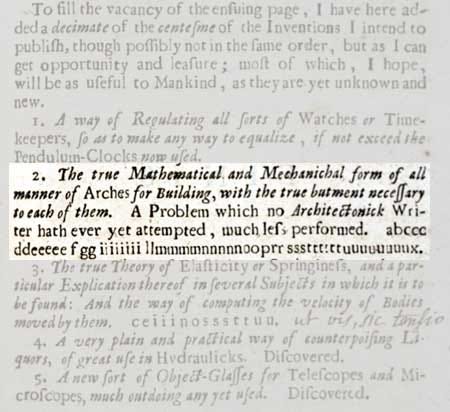

Now, onto more real-world things. Robert Hooke discovered that the catenary described both the ideal shape for a rope under its own weight, and an arch under its own weight. This was first published cryptically as an anagram (in Latin, no less!) with the solution to be released after his death.

The original anagram was this:

In plain English: An arch stands similarly to how a rope hangs.

Unsurprisingly, there’s no record of any contemporaries solving this in Hooke’s lifetime.

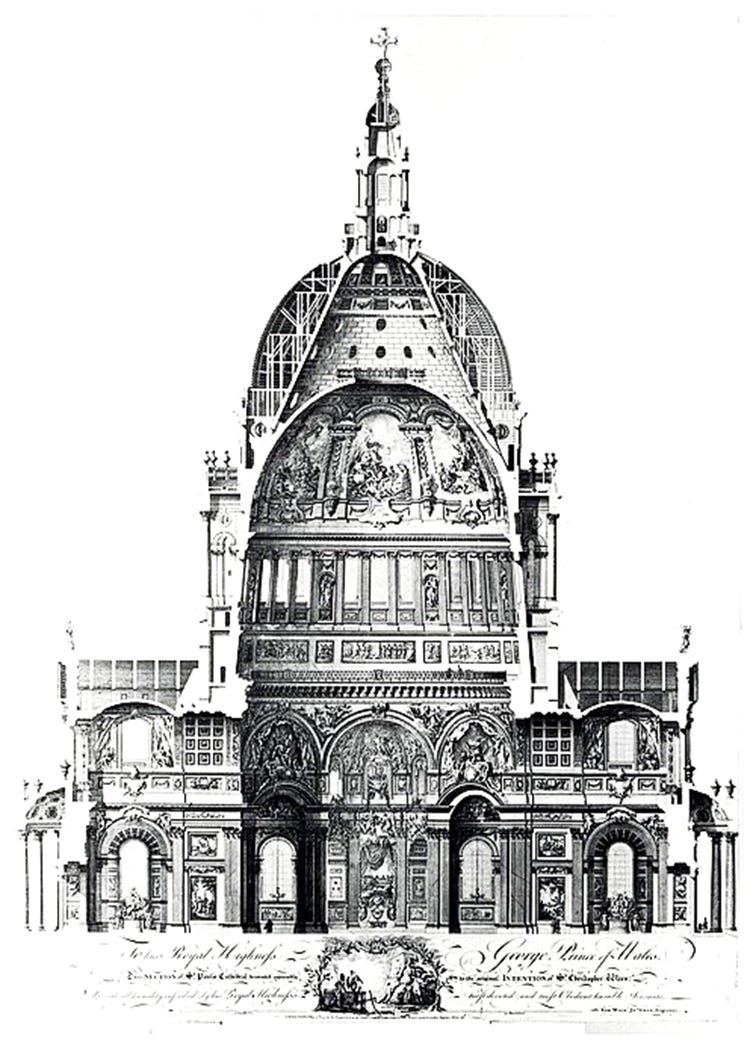

He and Christopher Wren used the curve when designing the domes for St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Athough, at the time, they thought the catenary would be modelled best by a cubic equation, their intuition on the symmetry of hanging chains and ideal arches was correct. The actual equation was discovered about 20 years later.

A quick aside – the three domes of St Paul’s are a phenomenal piece of architecture: the outer dome fitted the external image of the cathedral, but would look grossly out of proportion from the inside, so a façade was made. The true challenge came with holding up the “lantern” tower on the top, weighing some 850 tonnes. Even with the more efficient shapes for the dome a third middle dome – more of a cone than a dome – was needed to support the weight. Truly incredible, especially for the 1600s.

You can still see the catenary in modern architecture, like the Sheffield Winter Garden, along with countless railway station rooves, bridges, and even igloos and kilns.

It’s also used when cutting large fabric panels for tents and sails, which reduces wrinkles when the panel is under tension. This helps stop pockets of water forming on a tent in the rain, and makes the sail a much better aerofoil, upping efficiency.

Another place they’re seen is with charged particles moving through electric fields. While, at low velocities, they appear to move on parabolas, when sped up to relativistic speeds the path followed can be better approximated with a catenary, since the path is then trying to minimise energy under constraints.

Oh, and the last one is rotating it around an axis to make a sort of curved hourglass shape. That’s the shape between two circles with the least possible surface area – so curvy cylinder bubbles between two rings, or those collapsible tubes that young children crawl through.

Non-Catenary Arches

If the catenary is mathematically the best arch possible, how come other arches are so often used? Well, the answer to that is partly that it isn’t strictly always the best possible arch. In isolation, holding only its own weight, it absolutely is. The maths doesn’t lie on that front. However, if you then want to stack a couple storeys of building on top of it, or even a particularly heavy roof, or something else, the curve stops being optimal because its weight isn’t evenly distributed anymore. Gothic architecture made use of taller ogival arches (pointed arches), partly for the visual elegance, but also to hold up extremely heavy ceilings. Ribs and vaulted ceilings also helped with the technical challenges of that age.

Since older buildings were largely built using traditional masonry, the materials used couldn’t be placed under tension. The advent of structural steel, among other modern materials, has largely eliminated the need for arches to build large buildings, and so the modern preference for big rectangular sheets of glass has led to cities full of buildings with right-angles on every corner.

Finally, a modern example of an almost-catenary is this:

As someone who already knows this would gladly tell you, the Gateway Arch in St Louis isn’t quite a catenary, because it’s thinner and lighter at the top, so the shape is a little flattened to compensate. Either way, it’s a very good visual example, not least because, at 192m (630ft) high, you can hardly miss it!

Now, try and go through an ordinary day without seeing any catenaries anywhere – I guarantee it’s impossible. You might not recognise them, but they’re definitely there.